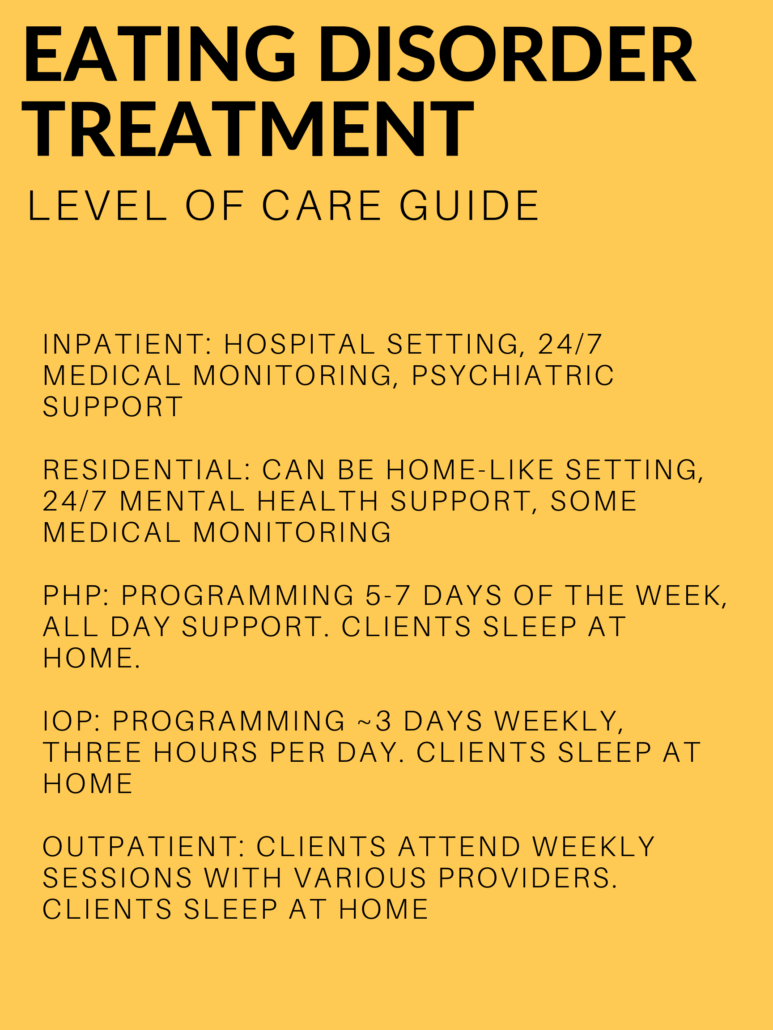

Eating Disorder Treatment: Levels of Care

written by Meagan Mullen, MA, MHC, Clinician and Community Outreach Specialist

Entering treatment for an eating disorder can be scary—no matter what level of care you’re embarking on. What can feel even more overwhelming, though, is trying to understand the differences between levels of care and what each entail.

To make it easier, we are going to take a look at the different levels of care one by one, including details about how the different levels can be helpful to people with eating disorders.

Inpatient Treatment

This is the highest level of care. Inpatient treatment, or inpatient hospitalization, can be beneficial when someone requires 24/7 medical supervision. This may be due to vital signs, lab findings, and other complications. Clients who need inpatient treatment might be struggling with other psychiatric issues, such as suicidal ideation or mood disturbances.

Inpatient treatment often occurs in a hospital-like setting, and clients are typically supported by both medical and mental health staff. This level of care provides clients with round-the-clock support as they work to become more medically stable and ready for a lower level of treatment. People receiving inpatient care can often need intravenous fluids (IVs), daily bloodwork, or other monitoring to ensure their medical safety. Clients sleep on an inpatient unit until they are discharged.

Residential Treatment

This level of care is when someone does not need round-the-clock medical monitoring, but still needs a high level of support to avoid behavior use. Residential treatment operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. In residential treatment, clients will partake in group therapy, individual therapy, and nutrition therapy, along with scheduled free time and opportunities for visits from family and friends. People in residential treatment have access to nursing staff 24/7 and are medically monitored, but they are considered medically stable enough to not need IVs, daily bloodwork, or other medical assistance. Residential treatment can occur in a home-like setting, and clients sleep at the treatment center location until discharge.

Partial-hospitalization Program (PHP): A PHP is intended for clients who do not need round-the-clock support, but who still need structure to avoid behavior use. PHPs typically run during normal business hours for 5-7 days per week. Clients in a PHP program sleep off site—either at home or in supportive living arrangements that are in conjunction with the treatment center they are attending. These supportive living arrangements offer more independence than residential treatment, but still offer support for clients when needed.

In a PHP, clients engage in group and individual therapy, and often in nutrition therapy. Some PHP programs offer medical monitoring, but this can vary from program to program.

Intensive-Outpatient Programs (IOP): Intensive-outpatient Programs are for clients who need more support than an outpatient team, but who do not need as much support as a PHP or residential program. Clients in IOPs sleep at home and partake in programming only a few days per week.

IOPs typically offer three days per week for a few hours, and evening programming is often available. This level of care can be beneficial for clients who are in school or working and do not require daily support. Clients in IOPs typically partake in individual therapy, group therapy, and a supported meal.

Outpatient: Outpatient support is the lowest level of support and often provides the most flexibility for clients. Often, clients will have an outpatient team, consisting of different professionals to support different aspects of recovery. MEDA often recommends working with an outpatient therapist who specializes in eating disorders, a dietitian who specializes in eating disorders, and maintaining regular contact with a primary care provider. Additionally, some clients benefit from working with a psychiatrist to prescribe any needed medication.

Clients can benefit from varying levels of care throughout their recovery, and often, clients find it beneficial to “step down” or “step up” a level depending on how much support is needed. If you have any questions about the various levels of care, a MEDA clinician can help.